Sin and confession: Newsrooms revisit some major failures

/The Washington Post on Nov. 12 took the highly unusual step of overhauling two articles that had been posted on its website since 2017 and 2019, respectively. Recent events had suddenly called into question the accuracy of the articles, which reported on the identity of a confidential source who supposedly contributed salacious information about Donald Trump that was contained in the infamous and since discredited “Steele dossier.” The Post removed large portions of the articles, changed the headlines, removed a companion video, and appended editor’s notes. About a dozen other, related stories were corrected, as well. The Post’s editor offered public explanations on various platforms.

This got me to thinking about previous famous situations in which a news organization belatedly found fault with its coverage of a high-profile subject and decided it needed to take corrective action. I’m not thinking about individual stories that proved faulty – though there are many – nor am I thinking about discoveries of plagiarism and fabrication committed by reporters (Janet Cooke, Jayson Blair, Stephen Glass, Jonah Lehrer, Jack Kelly, Mike Barnicle -- shall I stop now?)

Rather, I have in mind organizations that took a retrospective look at months or even years of stories on a subject and found overall coverage to be flawed if not disgraceful, leading to publication of an honest self-assessment or apology. Here are just some:

In 1990, The New York Times asked one of its writers to revisit the work of Walter Duranty, the Times’ Moscow correspondent from 1922 to 1936. Duranty was an apologist for Joseph Stalin, and essentially ignored a Ukrainian famine that killed millions in 1930-31. Yet he won a Pulitzer Prize in 1934. The writer concluded that Duranty produced “some of the worst reporting to appear in this newspaper. … Having bet his reputation on Stalin, he strove to preserve it by ignoring or excusing Stalin's crimes. He saw what he wanted to see.”

In 2004, the Times admitted to significant failures in its coverage leading up to the war in Iraq during the George W. Bush administration. Many reported facts in support of a war were untrue, and the Times faulted multiple reporters’ overreliance on non-credible information from “Iraqi informants, defectors and exiles bent on 'regime change’ in Iraq.” The editors wrote, “Looking back, we wish we had been more aggressive in re-examining the claims as new evidence emerged – or failed to emerge.”

The Washington Post’s media critic wrote a similar piece about the war in 2004, framing the problem as lack of prominence for stories with dissenting voices. It quoted then assistant managing editor Bob Woodward: "We should have warned readers we had information that the basis for this (war) was shakier" than commonly understood. "Those are exactly the kind of statements that should be published on the front page."

Perhaps no subject is more suited for media self reflection than reporting on race and the civil rights movement.

In 2004, The Lexington Herald-Leader published a front-page editor’s note that would almost be funny if it weren’t so unfunny: "It has come to the editor's attention that the Herald-Leader neglected to cover the civil rights movement. We regret the omission." The newspaper wasn’t being flippant. It also published a collection of articles examining past coverage of local civil rights activities, which were usually ignored or relegated to the back pages. According to a Washington Post story, news about the Lexington Black community appeared mainly in a column called “Colored Notes” written by the newsroom’s only Black employee. (My former employer, The Birmingham News, engaged in this same approach to coverage during this era. It acknowledged its failings in print in 1988.)

Much more recently, in April 2018, the editorial board of The Montgomery Advertiser published “Our shame: The sins of our past laid bare for all to see.” It wrote: “The Advertiser was careless in how it covered mob violence and the terror foisted upon African-Americans from Reconstruction through the 1950s. We dehumanized human beings. Too often we characterized lynching victims as guilty before proven so and often assumed they committed the crime.” The paper heard from some readers “who wish we would leave the past in the past. We can’t do that.”

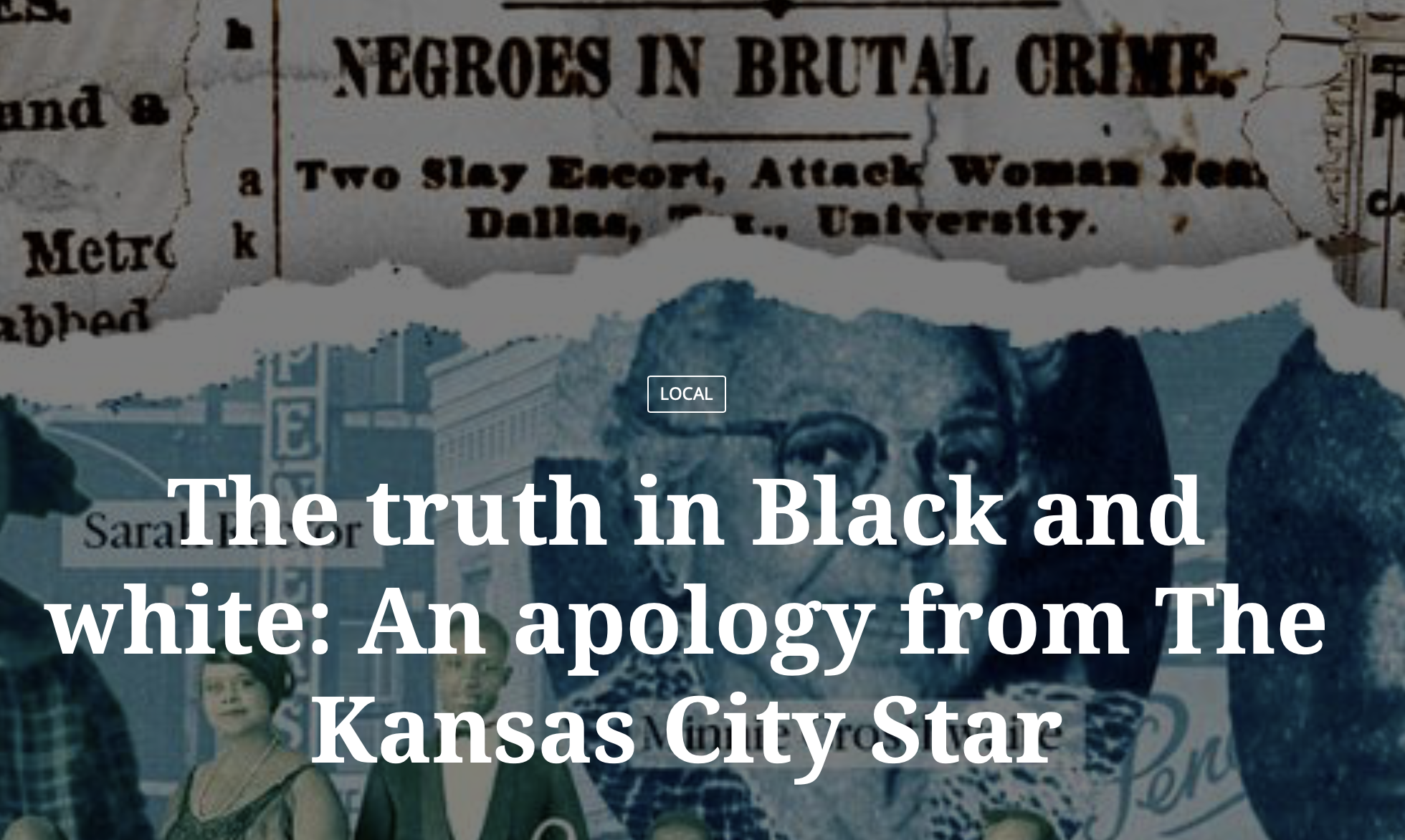

The Kansas City Star researched its archives back to its founding in 1880 and compared its coverage to local Black-owned media. It published an apology in December 2020. The Star “disenfranchised, ignored and scorned generations of Black Kansas Citians. It reinforced Jim Crow laws and redlining. Decade after early decade it robbed an entire community of opportunity, dignity, justice and recognition.”

These mea culpas are painful. But ethical news media do them when necessary. It’s not mere public relations. It’s accountability to the public, even if it’s late, even if damage can’t be undone.

The next question, of course, is what coverage is happening now that will someday be the focus of yet more regretful confessions. Preferably, the news media will do enough immediate self-examination to render them unnecessary.