Damar Hamlin’s horrifying collapse gives some football writers pause

/ESPN PHOTO

I’m well aware of the many ways I benefitted in my years as a sports journalist from the popularity of football. That’s true for all the sports media that report on, and therefore indirectly promote, football at any level.

More readership and ratings. More status and money.

It’s all good until a moment comes along that demands a look in the mirror and an answer to the question “Should I really be doing this?”

I saw some of that in the aftermath of Monday night’s horrifying collapse of Buffalo Bills football player Damar Hamlin seconds after a normal tackle on live national TV. Emergency medical staff administered CPR and electrical shock while players kneeled and prayed and cried. Fans in the stadium hushed.

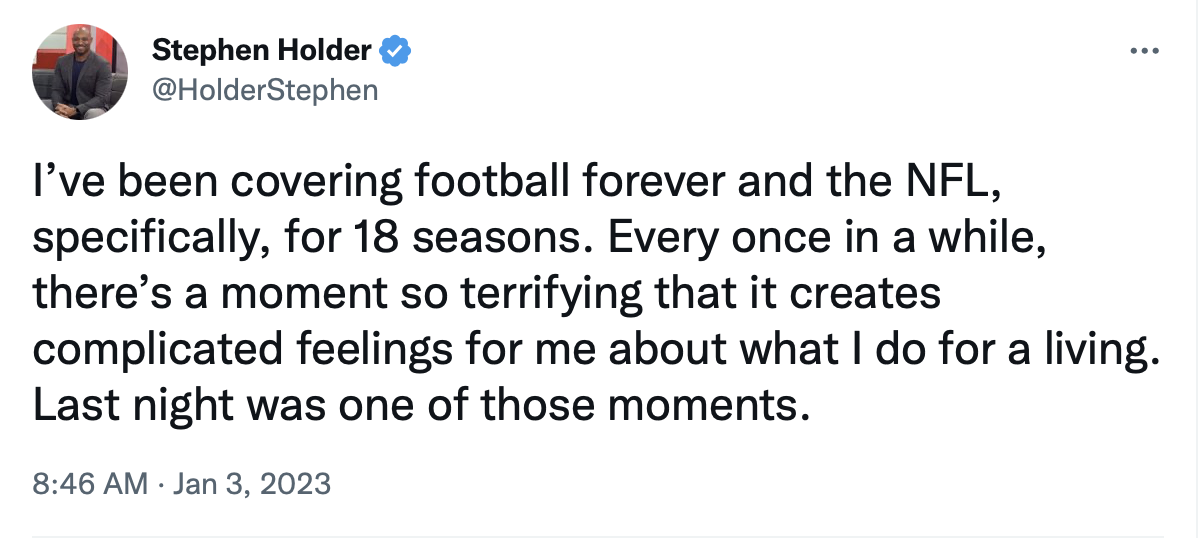

Stephen Holder of ESPN tweeted the next morning: “I’ve been covering football forever and the NFL, specifically, for 18 seasons. Every once in a while, there’s a moment so terrifying that it creates complicated feelings for me about what I do for a living. Last night was one of those moments.” In response to a reader comment, he added: “I love football. That won’t change.”

No doubt many writers who make a living from this enjoyable but dangerously physical sport share those complicated feelings right now.

“It’s often difficult for me to reconcile this business and this sport with real life and humanity,” tweeted Gregg Bell, who covers the Seattle Seahawks for the Tacoma News Tribune (and was a great guest speaker to the Tuscaloosa chapter of the Associated Press Sports Editors last year). In a podcast with a Seattle radio station, he said the possibility that an athlete might have died as a result of a hit in a game “shook us to the core.”

The sport creates multiple episodes of trauma every season on every level, though not necessarily with the same potential life-or-death consequences as Monday night. See, for instance, the two concussions – that means a brain injury – sustained by former UA and current Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa within three months of each other this season.

But it’s not just the obvious, catastrophic collisions that raise questions about the safeness of football. A growing volume of research indicates that an accumulation of sub-concussive hits – that means routine contact – can cause brain damage that slowly shows itself in later years.

Decision-makers in the sport have made many changes to rules and equipment to try to make the game safer. And players understand the risks. But for people who see the big picture, such as sports journalists, that doesn’t remove the question of whether they should give attention and promotion to a sport of such great potential harm to its participants – all for the sake of profit and entertainment.

“Honestly? This is the Faustian bargain every one of us who watches/writes about/talks about football has made for a long time,” tweeted St. Bonaventure journalism professor Brian Moritz while Hamlin was being resuscitated. A Faustian bargain means sacrificing a moral value for a material gain. (Moritz writes a very good sports journalism blog, by the way.)

In 2017, one sports journalist decided he wasn’t going to accept that bargain anymore.

Ed Cunningham, a former NFL player who was a college football analyst for ESPN, quit the job because he said he could no longer play his supporting role for a sport that was injuring or gradually killing some of its players, including some former teammates. “I just don’t think the game is safe for the brain,” he told the New York Times. “To me, it’s unacceptable.”

Football reporters in recent years have embraced a good but less drastic action: Including stories about the sport’s dangers as part of their overall coverage. It is common to see reports about injury protocol compliance, or the latest neurology research, or the deteriorating life of a former player. Some advocate for new safety measures, too.

As excellent as that is, there’s not much time or space in the media for the viewpoint – a minority viewpoint, for sure – that the game needs fundamental change. Every sport carries risks, of course, but only a few – football and boxing, for instance – build dangerous physical contact into their essence.

Calls for less tackle football and more flag football are understandably focused on levels before high school. I don’t think participants, fans or the sports media would entertain anything more radical, because that would mess with a whole lot of golden geese.

I and many others will watch the games as usual this weekend and next Monday, and reporters will cover them. In the wake of this Monday’s harrowing events, none of that will be as easy as it once was.