A demon and a Lemon: Big-name firings were not the same

/You ought to do some soul-searching if you’re a big-time media figure who gets fired and the media reporters have to offer possible reasons in list form.

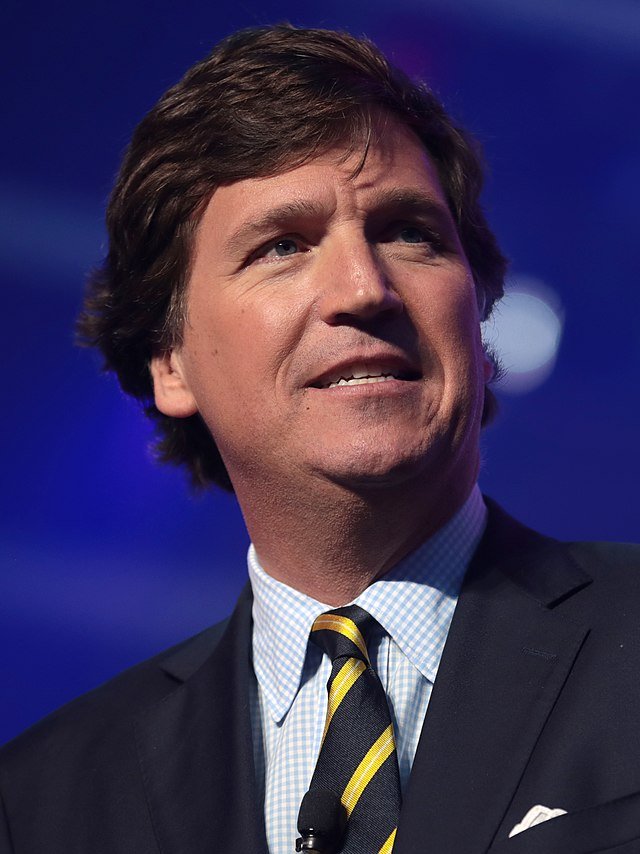

But that won’t happen with Tucker Carlson, who, despite being fired by MSNBC, CNN and now Fox, is incapable of shame. And maybe couldn’t find his soul anyway.

One remarkable aspect is that Fox even did this to its biggest ratings winner. I feel certain it was not because of anything Carlson said on air because he crossed any boundaries that might exist a long time ago. It may well have sprung from offensive comments off the air about top Fox executives. But almost certainly it had something to do with money.

Fox may have decided he’s a legal liability, since he mightily bolstered the Dominion Voting System lawsuit against the network and attracted another lawsuitt from a former “Tucker Carlson Tonight” producer who claimed Carlson and other show executives created a hostile work environment for women.

Which brings up another remarkable aspect: The continuing self-destruction of male national TV news stars due to credible allegations of sexual assault or harassment. I can think of Carlson (hostile environment is a form of harassment), Bill O’Reilly, Chris Cuomo, Matt Lauer, Charlie Rose, Chris Matthews, Mark Halperin, Eric Bolling and Ed Henry. Phew, I gotta rest. Don Lemon too, although he didn’t get fired at the time.

Obviously, abhorrent behavior like this takes place in all kinds of fields and institutions. But I think a heady combination of ratings, fame, ego, money and power leads to the feeling that they can do whatever they want to whichever subordinate they want – and are even entitled to it.

And in the case of someone like Carlson, when your nightly job is to denigrate the less powerful groups of society, it’s only a short step to practicing misogyny in your real life.

I’ve written about Fox News before (here and here). With its history, Fox may be more mindful of its treatment of women today, but I hold no hope that Carlson’s firing signals a lasting change to the dreck it churns out on its primetime opinion shows.

As for Carlson, in older days when there were only three, over-air networks, he’d have nowhere else to go. But today there’s always a right-wing cable network or website or podcast that’s got a bad agenda and no standards. In other words, the only kind of medium where Carlson could work.

Don Lemon

The longtime, opinionated CNN anchor got fired the same day Carlson did. But Lemon’s ouster was a bad decision.

Yes, Lemon said stupid and offensive stuff too often. But if media reports are correct that he was fired for violating CNN policy against challenging Republican guests on its shows, that’s a black mark for CNN’s new leadership. Maybe don’t call out your own control room as Lemon did, but pushing back is exactly what interviewers are supposed to do.